lesser developed middle

Keys, too, and the lucky shell prospector might come up with a bonanza

there. lesser developed middle

Keys, too, and the lucky shell prospector might come up with a bonanza

there.Access to warm currents may be a significant factor in why certain beaches are good for collecting shells. In warm climates, shell-bearing animals can develop their protective cases in leisure, layer upon layer. Animals in cold water have to hurry up the shielding process in order to put more energy into other tasks, like burning up calories to stay warm. Thus fortified by thicker walls, shells born in the tropics have a better chance of withstanding the pounding surf, so that when they are rolled up to shore by the waves they are intact and collectible. This may be one reason why fossil mollusks--which are also abundant in Florida--have very thick shells. They formed at a time when the environment was generally much warmer than it is now. If you're the organized type and like to classify your shells, there are two ways of doing it. One way is to divide them into shells that come from the deep waters (abyssal) ,those which spent most of their life afloat on the sea (pelagic) or those which live close to the shore (littoral). Scientists have found an even better way of classifying shells, and that is to examine the kind of foot, or locomotive apparatus, the living creature employs. Using this method of differentiation, there are six kinds of mollusks. Most shelly creatures fall into two of these categories.

Stomach Feet...

...and Hatchet FeetGastropods are univalves formed of one shell. Clams, mussels, oysters, and their cousins are bivalves--two-shelled creatures. Their feet do not crawl, they dig, like shovels; thus their sceintific name Pelecypoda, meaning "hatchet footed." Lacking eyes or the heads to rest them on, most Pelecypods lead quiet lives near their parents in shell towns known as "beds". Oysters can live up to 30 years and clams about 20, provided nothing much happens to them. Few actually get to live out their life expectancy, however, because most occupants of "Shell Town" eventually fall prey to more complex strangers, like gastropods or enchinoderms (starfish). An exception to this rule is the scallop family. Scallops are the rocket scientists of the Pelecypod world. Adult scallops are pelagic, propelling themselves through the seas by opening and shutting their shells in a rapid series of bursts, not unlike tiny fire bellows. They have a row of tiny eyes on their mantle (the thin film that envelops their fleshy parts, analogous to our skin), each eye complete with cornea, lens and optic nerve. Another group of pelecypods that gets around are the lima clams, aka "file shells" of south Florida. A spiny file shell can use its foot to bounce up from the bottom and can swim, but file shells have no eyes, and as far as we can tell, no

files on where they've been. provided nothing much happens to them. Few actually get to live out their life expectancy, however, because most occupants of "Shell Town" eventually fall prey to more complex strangers, like gastropods or enchinoderms (starfish). An exception to this rule is the scallop family. Scallops are the rocket scientists of the Pelecypod world. Adult scallops are pelagic, propelling themselves through the seas by opening and shutting their shells in a rapid series of bursts, not unlike tiny fire bellows. They have a row of tiny eyes on their mantle (the thin film that envelops their fleshy parts, analogous to our skin), each eye complete with cornea, lens and optic nerve. Another group of pelecypods that gets around are the lima clams, aka "file shells" of south Florida. A spiny file shell can use its foot to bounce up from the bottom and can swim, but file shells have no eyes, and as far as we can tell, no

files on where they've been.

TusksThere is a small class of fragile shells called Scaphopods, or "plow-footed" shells, so named because they're well adapted to burrowing. Most collectors know them as "tusk" shells, because these long, tapering shells look like animal tusks. Most varieties like shallow water, but because they are so delicate, few make it to shore intact. If you could gather a few buckets of tusk shells and then time-warp back to pre-Columbian days, you would be rich. Native Americans of the Northeast used tusk shells imported from Florida as currency, along with the internal columns of channeled and knobbed whelk shells.

Living FossilsThe remaining classes of mollusk were much better represented 570,000,000 years ago or more than they are today. Chitons--commonly found stuck to rocks--have shells composed of eight overlapping plates that can contract and expand. Many paleontologists believe that the chiton was the prototype for all mollusks. The official name for their class is Amphineura.Natural history lovers will probably be familiar with ammonites, beautifully spiralled shellfish whose petrified remains are common in fossils originating from dinosaur times. Ammonites were Cephalopods, literally "head-footed". Octopi and squid are modern-day cephalopods, mollusks who, like slugs, have no external shells. One form of squid known as the "spirula" does, however, have a small internal shell that resembles a ram's horn. When the animal dies, its body falls away, and the snowy white shell floats to the surface, to be deposited on Florida shores and discovered by the lucky collector. An even luckier collector might find the rare Paper Argonaut, a shell that is actually used as a floating cradle for Argonaut eggs.

Rarest of the Rare So far we have

mentioned five classes of mollusks. The sixth class is rare indeed. The

cap-shaped shells of the Monoplacophora group were thought to be extinct

until about 40 years ago, when fishermen in Guatemala hauled one up from

the deep sea. The chance of finding one on your Florida vacation is pretty

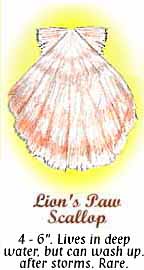

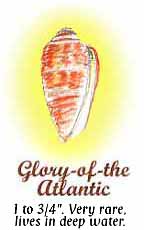

much nil. But you might find some other rare specimen. A

Glory-of-the-Atlantic Cone shell, only a little more than an inch tall,

does occur in South Florida waters and could bring you a tidy sum. So could

a Beau's Murex, a perfectly preserved Elegant Venus, or a Lion's Paw

scallop. So far we have

mentioned five classes of mollusks. The sixth class is rare indeed. The

cap-shaped shells of the Monoplacophora group were thought to be extinct

until about 40 years ago, when fishermen in Guatemala hauled one up from

the deep sea. The chance of finding one on your Florida vacation is pretty

much nil. But you might find some other rare specimen. A

Glory-of-the-Atlantic Cone shell, only a little more than an inch tall,

does occur in South Florida waters and could bring you a tidy sum. So could

a Beau's Murex, a perfectly preserved Elegant Venus, or a Lion's Paw

scallop.

A truly valuable personal shell collection, however, might not be one that can boast of a rare shell, but one that displays, in an elegant and instructional way, a wide variety of mollusks, shells collected over many years from many different beaches; one that holds for the collector as many lovely memories as it does beautiful shells... |

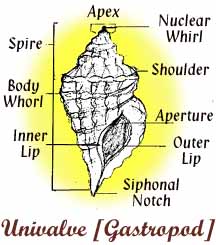

The largest is the

group comprising snails, slugs, and conchs. Did you ever look at a garden

slug and contemplate its ancestral affinity to a sea slug? How about to a

gorgeously spiky Fighting Stromb? No? All of them undulate themselves from

place to place on a massive, rippling foot and have eyes perched at the

ends of two soft, retractable stalks. They're called gastropoda, or

"stomach foot". The shells of gastropods grow from the bottom down, in one

continuous spiral. At the very top of the shell you can see the tiny

"nuclear whorl" of the shell's infant shell days. The longer the animals

live, the bigger their spirals-and thus their entire outer body-grow.

Some gastropods breathe with gills. Others have veins near their soft

body's surface that facilitate oxygen interchange with their environment.

The largest is the

group comprising snails, slugs, and conchs. Did you ever look at a garden

slug and contemplate its ancestral affinity to a sea slug? How about to a

gorgeously spiky Fighting Stromb? No? All of them undulate themselves from

place to place on a massive, rippling foot and have eyes perched at the

ends of two soft, retractable stalks. They're called gastropoda, or

"stomach foot". The shells of gastropods grow from the bottom down, in one

continuous spiral. At the very top of the shell you can see the tiny

"nuclear whorl" of the shell's infant shell days. The longer the animals

live, the bigger their spirals-and thus their entire outer body-grow.

Some gastropods breathe with gills. Others have veins near their soft

body's surface that facilitate oxygen interchange with their environment.

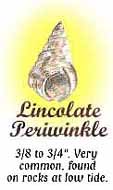

There is enormous

diversity among the univalves. Tiny periwinkles, found in profusion in

intertidal areas, are gastropods; as are giant tun shells from the deep

waters and the quiet limpets who cling to rocks at low tide. Also whelks, whose family members are among the most common finds on Florida beaches, and the murex, whose glands secrete a dye once used to color the robes of kings, Tyrian purple. The Crown Conch is a voraciously

predatory gastropod, whose foot has evolved something like a claw; the gorgeous pink and cream-colored Queen's Stromb is said to use the spines on the top of its shell to overwhelm its opponents, on whom it then dines.

Some members of the Cone shell family have harpoon-like teeth filled with venom that paralyzes its victims. (There's no record of Florida's indigenous Cone shells attacking humans, but be careful if you find one of

these colorful but dangerous animals.)

There is enormous

diversity among the univalves. Tiny periwinkles, found in profusion in

intertidal areas, are gastropods; as are giant tun shells from the deep

waters and the quiet limpets who cling to rocks at low tide. Also whelks, whose family members are among the most common finds on Florida beaches, and the murex, whose glands secrete a dye once used to color the robes of kings, Tyrian purple. The Crown Conch is a voraciously

predatory gastropod, whose foot has evolved something like a claw; the gorgeous pink and cream-colored Queen's Stromb is said to use the spines on the top of its shell to overwhelm its opponents, on whom it then dines.

Some members of the Cone shell family have harpoon-like teeth filled with venom that paralyzes its victims. (There's no record of Florida's indigenous Cone shells attacking humans, but be careful if you find one of

these colorful but dangerous animals.)